Instead of jail, judge orders Islamic State terrorist to ‘rehab’

Can a Muslim fanatic who wanted to join ISIS be “de-radicalized” so that he’s no longer a threat to society?

Can a Muslim fanatic who wanted to join ISIS be “de-radicalized” so that he’s no longer a threat to society?

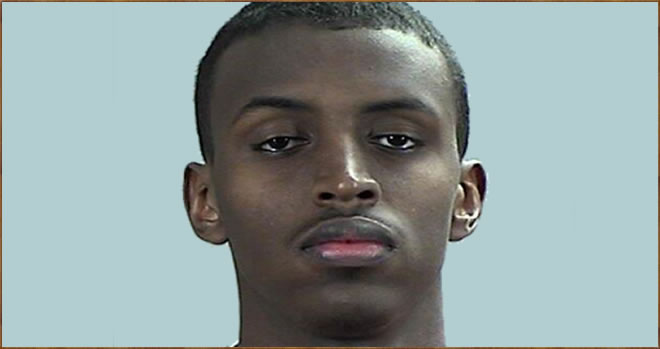

A Minnesota judge thinks so. He ordered Abdullahi Yusuf, who pleaded guilty to giving material support to terrorism, to leave jail and report to a halfway house where a counselor would presumably deprogram him.

Oh – the halfway house has absolutely no experience in “deradicalizing” Muslim terrorists.

Abdullahi Yusuf of Minnesota was allowed to depart from jail and stay at a halfway home after he pleaded guilty to conspiring to provide material support to the so-called Islamic State widely known as ISIS in January. (Yusuf was stopped at the airport trying to fly to Turkey in May 2014, at age 18.) Once inside the halfway home, Yusuf was to be “de-radicalized” through regular meetings with a counselor whose curriculum looked more like a high-school civics course than religious deprogramming.

His attorney proposed the de-radicalization program and Judge Michael Davis approved it over prosecutors’ objections. In a memorandum, the assistant U.S. attorneys trying Yusuf’s case reiterated their concerns about this program for Yusuf, because they said he had evaded his parents’ supervision and lied to authorities. Nevertheless, Judge Davis released him with an electronic monitoring device around his ankle.

Yusuf was assigned a bed at a halfway house in St. Paul where he could only leave for approved activities—like meetings with his mentors from a civics group called Heartland Democracy.

Heartland director Mary McKinley said she was not exactly sure why Yusuf’s proposal was granted, other than maybe it “just made sense.”

“On the other hand, it was also a surprise that any kind of access was given,” she said. “But I think it says a lot about what the U.S. attorney and the community were trying to do.”

Heartland had no prior experience with de-radicalizing jihadis, and it was carrying out the government’s first foray into deradicalizing ISIS sympathizers. While government-sanctioned de-radicalization programs for jihadis have existed for years in Canada, Europe, and even Saudi Arabia, the U.S. never faced large numbers of homegrown jihadists until the rise of ISIS. (More than 60 people have been arrested for, charged with, or convicted of ISIS-related crimes so far.)

The idea that an organization with no experience in deprogramming radicals is given the task of reforming terrorist sympathizers is just plain loony. But the concept itself may have some merit. Other countries report up to a 90% success rate in mainstreaming prisoners convicted of nonviolent terrorist crimes. And when you consider the probability that the prisoner would be further radicalized in prison, it makes sense to look for an alternative.

But does this touchy-feely approach really work?

Painting sessions at the Mohammad Bin Nayef Center for Advice, Counseling and Care are revelatory. A piece by one patient — referred to as a “beneficiary” — shows green trees and a bright blue lake at the foot of a jagged mountain.

The bucolic-seeming scene is of the Tora Bora mountains in Afghanistan where Osama bin Laden and his fighters eluded capture by American special forces months after the 9/11 attacks on the United States.

“This guy has been to Tora Bora,” art therapist Awad al-Yami told NBC News. His patient’s time in the network of mountain caves on the border with Pakistan were full of danger, deprivation and fear, according to al-Yami.

“It is their suffering that they are bringing out, and the art is giving them a chance to express their suffering and feelings,” the therapist said.

Al-Yami’s patients are part of a de-radicalization program aimed at integrating Saudi citizens who have tried to join the ranks of ISIS and al Qaeda.

Clerics, psychologists, sociologists, art therapists, sports instructors and teachers work to incorporate the so-called beneficiaries’ families and former employers into the process of reintegrating the men into mainstream society.

While the center only works with those who haven’t been convicted of a violent crime, the experts who work there take their charges and their ideology very seriously.

“This is a dangerous place, said sociologist Ahmed al-Shehri, noting that all 50 clients have an “extremist” background. “But we invest in them,” he added.

Sorry, but good intentions get you squat when you’re dealing with someone who was perfectly willing to kill people for their religion. What needs to change is the person’s religious beliefs, not their psyche. And to ask a Wahhabist cleric to teach anything that would alter a terrorist’s perspective on jihad is wishful thinking.

I would have no problem with such “interventions” conducted in prison. Anything is worth a try when the subject is safely locked away. But this plan – if tried on other would-be terrorists – is too much of a gamble to take.