USA to Issue More Green Cards Than Populations of Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina Combined

The overwhelming majority of immigration to the United States is the result of our visa policies. Each year, millions of visas are issued to temporary workers, foreign students, refugees, asylees, and permanent immigrants for admission into the United States. The lion’s share of these visas are for lesser-skilled and lower-paid workers and their dependents who, because they are here on work-authorized visas, are added directly to the same labor pool occupied by current unemployed jobseekers. Expressly because they arrive on legal immigrant visas, most will be able to draw a wide range of taxpayer-funded benefits, and corporations will be allowed to directly substitute these workers for Americans. Improved border security would have no effect on the continued arrival of these foreign workers, refugees, and permanent immigrants—because they are all invited here by the federal government.

The most significant of all immigration documents issued by the U.S. is, by far, the “green card.” When a foreign citizen is issued a green card it guarantees them the following benefits inside the United States: lifetime work authorization, access to federal welfare, access to Social Security and Medicare, the ability to obtain citizenship and voting privileges, and the immigration of their family members and elderly relatives.

The most significant of all immigration documents issued by the U.S. is, by far, the “green card.” When a foreign citizen is issued a green card it guarantees them the following benefits inside the United States: lifetime work authorization, access to federal welfare, access to Social Security and Medicare, the ability to obtain citizenship and voting privileges, and the immigration of their family members and elderly relatives.

Under current federal policy, the U.S. issues green cards to approximately 1 million new Legal Permanent Residents (LPRs) every single year. For instance, Department of Homeland Security statistics show that the U.S. issued 5.25 million green cards in the last five years, for an average of 1.05 million new legal permanent immigrants annually.

These ongoing visa issuances are the result of federal law, and their number can be adjusted at any time. However, unlike other autopilot policies—such as tax rates or spending programs—there is virtually no national discussion or media coverage over how many visas we issue, to whom we issue them and on what basis, or how the issuance of these visas to individuals living in foreign countries impacts the interests of people already living in this country.

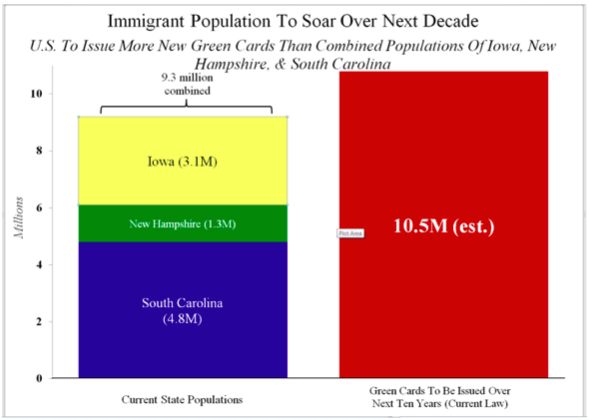

If Congress does not pass legislation to reduce the number of green cards issued each year, the U.S. will legally add 10 million or more new permanent immigrants over the next 10 years—a bloc of new permanent residents larger than populations of Iowa, New Hampshire, and South Carolina combined.

This has substantial economic implications.

The post-World War II boom decades of the 1950s and 1960s averaged together less than 3 million green cards per decade—or about 285,000 annually. Due to lower immigration rates, the total foreign-born population in the United States dropped from about 10.8 million in 1945 to 9.7 million in 1960 and 9.6 million in 1970.

These lower midcentury immigration levels were the product of a federal policy change: after the last period of large-scale immigration that had begun in roughly 1880, immigration rates were lowered to reduce admissions. The foreign-born share of the U.S. population fell for six consecutive decades, from 1910 through 1960.

Legislation enacted in 1965, among other factors, substantially increased low-skilled immigration. Since 1970, the foreign-born population in the United States has increased more than four-fold—to a record 42.1 million today. The foreign-born share of the population has risen from fewer than 1 in 21 in 1970, to presently approaching 1 in 7. As the supply of available labor has increased, so too has downward pressure on wages.

Georgetown and Hebrew University economics professor Eric Gould has observed that “the last four decades have witnessed a dramatic change in the wage and employment structure in the United States… The overall evidence suggests that the manufacturing and immigration trends have hollowed-out the overall demand for middle-skilled workers in all sectors, while increasing the supply of workers in lower skilled jobs. Both phenomena are producing downward pressure on the relative wages of workers at the low end of the income distribution.”

During the low-immigration period from 1948-1973, real median compensation for U.S. workers increased more than 90 percent. By contrast, real average hourly wages were lower in 2014 than they were in 1973, four decades earlier. Harvard Economist George Borjas also documented the effects of high immigration rates on African-American workers, writing that “a 10 percent immigration-induced increase in the supply of workers in a particular skill group reduced the black wage of that group by 2.5 percent.” Past immigrants are additionally among those most economically impacted by the arrival of large numbers of new workers brought in to compete for the same jobs. In Los Angeles County, for example, 1 in 3 recent immigrants are living below the poverty line. And this federal policy of new large-scale admissions continues unaltered at a time when automation is reducing hiring, and when a record share of our own workers here in America are not employed.

President Coolidge articulated how a slowing of immigration would benefit both U.S.-born and immigrant-workers: “We want to keep wages and living conditions good for everyone who is now here or who may come here. As a nation, our first duty must be to those who are already our inhabitants, whether native or immigrants. To them we owe an especial and a weighty obligation.”

It is worth observing that the 10 million grants of new permanent residency under current law is not an estimate of total immigration. In fact, the increased distribution of legal immigrant visas tend to correlate with increased flows of immigration illegally: the former helps provide networks and pull factors for the latter. Most of the countries who send the largest numbers of citizens with green cards are also the countries who send the most citizens illegally. The Census Bureau estimates 13 million new immigrants will arrive, on net, between now and 2024—hurtling the U.S. past all recorded figures in terms of the foreign-born share of total population, quickly eclipsing the watermark recorded 105 years ago during the 1880–1920 immigration wave before immigration rates were lowered. Absent new legislation to reduce unprecedented levels of future immigration, the Census Bureau projects immigration as a share of population will continue setting new records each year, for all time.

Yet the immigration “reform” considered by Congress most recently—the 2013 Senate “Gang of Eight” comprehensive immigration bill—would have tripled the number of green cards issued over the next 10 years. Instead of issuing 10 million green cards, the Gang of Eight proposal would have issued at least 30 million green cards during the next decade (or more than 11 times the population of the City of Chicago).

Polling from Gallup and Fox shows that Americans want lawmakers to reduce, not increase, immigration rates by a stark 2:1 margin. Reuters puts it at a 3:1 margin. And polling from GOP pollster Kellyanne Conway shows that by the huge margin of nearly 10:1 people of all backgrounds are united in their belief that U.S. companies seeking workers should raise wages for those already living here—instead of bringing in new labor from abroad.

https://t.me/s/Official_1win_kanal/1281