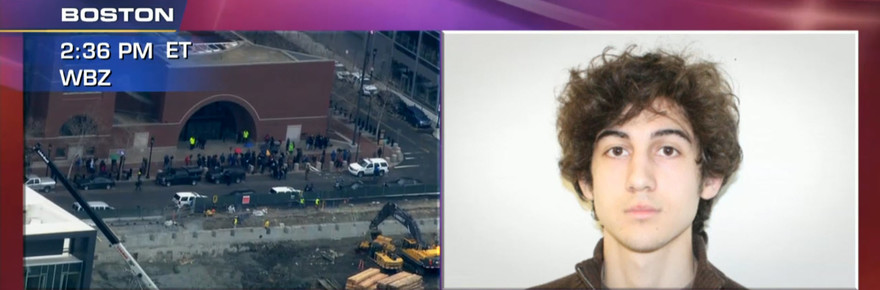

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev found guilty on all counts in Boston Marathon bombing

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev was convicted Wednesday in the Boston Marathon bombing by a federal jury that now must decide whether he should be executed.

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev was convicted Wednesday in the Boston Marathon bombing by a federal jury that now must decide whether he should be executed.

The verdict was reached Wednesday afternoon, nearly two years to the day three people were killed and more than 260 injured in the April 15, 2013, bombings.

Tsarnaev, 21, showed no emotion as he listened to the verdict, reached after a day and a half of deliberations. He was found guilty on all 30 counts that included conspiracy and use of a weapon of mass destruction — offenses punishable by death.

His conviction was practically a foregone conclusion, given his lawyer’s startling admission during opening statements that Tsarnaev carried out the attack with his now-dead older brother, Tamerlan.

The two shrapnel-packed pressure-cooker bombs that exploded near the finish line, turning the traditionally celebratory home stretch of the world-famous race into a scene of carnage and putting the city on edge for days.

In the next phase of the trial, the jury will hear evidence on whether Tsarnaev should get the death penalty or spend the rest of his life in prison.

“It’s not a happy occasion, but it’s something,” said Karen Brassard, who suffered shrapnel wounds on her legs and attended the trial. “One more step behind us.”

She said Tsarnaev appeared “arrogant” and uninterested during the trial, and she wasn’t surprised when she saw no remorse on his face as the verdicts were read. She refused to say whether she believes he deserves the death penalty, but she rejected the defense argument that he was simply following his brother’s lead.

“He was in college. He was a grown man who knew what the consequences would be,” Brassard said.

Tsarnaev’s lawyers left the courthouse without comment.

In a bid to save Tsarnaev from a death sentence, defense attorney Judy Clarke has argued that Tsarnaev, then 19, fell under the influence of his radicalized brother. Tamerlan, 26, died when he was shot by police and run over by his brother during a chaotic getaway attempt days after the bombing.

“If not for Tamerlan, it would not have happened,” Clarke told the jury during closing arguments.

Prosecutors, however, portrayed the brothers — ethnic Chechens who moved to the U.S. from Russia more than a decade ago — as full partners in a plan to punish the U.S. for its wars in Muslim countries. Jihadist writings, lectures and videos were found on both their computers, though the defense argued that Tamerlan downloaded the material and sent it to his brother.

The government called 92 witnesses over 15 days, painting a hellish scene of torn-off limbs, blood-spattered pavement, ghastly screams and the smell of sulfur and burned hair. Survivors gave heartbreaking testimony about losing legs in the blasts or watching people die. The father of an 8-year-old boy described making the agonizing decision to leave his mortally wounded son so he could get help for their 6-year-old daughter, whose leg had been blown off.

Killed were Lingzi Lu, a 23-year-old Chinese graduate student at Boston University; Krystle Campbell, a 29-year-old restaurant manager; and Martin Richard, the 8-year-old. Massachusetts Institute of Technology police Officer Sean Collier was shot and killed during the brothers’ getaway attempt.

In a statement, Collier’s family welcomed the verdict and added: “The strength and bond that everyone has shown during these last two years proves that if these terrorists thought that they would somehow strike fear in the hearts of people, they monumentally failed.”

Some of the most damning evidence included video showing Tsarnaev planting a backpack containing one of the bombs near where the 8-year-old was standing, and incriminating statements scrawled inside the dry-docked boat where a wounded and bleeding Tsarnaev was captured days after the tragedy.

“Stop killing our innocent people and we will stop,” he wrote.

Tsarnaev’s lawyers barely cross-examined the government’s witnesses and called just four people to the stand over less than two days, all in an effort to portray the older brother as the guiding force in the plot.

Witnesses testified about phone records that showed Dzhokhar was at the University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth while his brother was buying bomb components, including pressure cookers and BBs. A forensics expert said Tamerlan’s computer showed search terms such as “detonator,” “transmitter and receiver,” while Dzhokhar was largely spending time on Facebook and other social media sites.

Also, an FBI investigator said Tamerlan’s fingerprints — but not Dzhokhar’s — were found on pieces of the two bombs.

Clarke is one of the nation’s foremost death-penalty specialists and has kept other high-profile defendants off death row. She saved the lives of Unabomber Ted Kaczynski and Susan Smith, the South Carolina woman who drowned her two children in a lake in 1994.

Tsarnaev’s lawyers tried repeatedly to get the trial moved out of Boston because of the heavy publicity and the widespread trauma. But opposition to capital punishment is strong in Massachusetts, which abolished its state death penalty in 1984, and some polls have suggested a majority of Bostonians do not want to see Tsarnaev sentenced to die.

During the penalty phase, Tsarnaev’s lawyers will present so-called mitigating evidence they hope will save his life. That could include evidence about his family, his relationship with his brother, and his childhood in the former Soviet republic of Kyrgyzstan and later in the volatile Dagestan region of Russia.

Prosecutors will present so-called aggravating factors in support of the death penalty, including the killing of a child and the targeting of the marathon because of the potential for maximum bloodshed.

Dan Collins, a former federal prosecutor who handled the case against a suspect in the 2008 terrorist attacks in Mumbai, India, said Massachusetts’ history of opposition to capital punishment will have no bearing on the jury’s decision about Tsarnaev’s fate.

“When you ask people their opinion of the death penalty, there are a number who say it should only be reserved for the horrific cases,” he said. “Here you have what is one of the most horrific acts of terrorism on U.S. soil in American history, so if you are going to reserve the death penalty for the worst of the worse, this is it.”

Liz Norden, the mother of two sons who lost parts of their legs in the bombing, said death would be the appropriate punishment: “I don’t understand how anyone could have done what he did.”