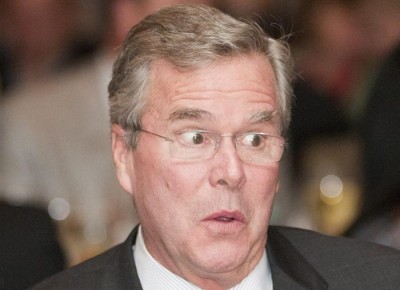

Nearly 75 Percent of Current Floridians Never Saw Jeb Bush’s Name on a Ballot

Jeb Bush’s big political credential, and his presumed strength in the presidential campaign he’ll launch on Monday, is the broad appeal he demonstrated over two terms as Florida governor—doubly important given the critical role Florida’s primary will play in winnowing the GOP field. Bush handily won his last race, in 2002, by drawing support from Republicans and Democrats with what even his opponents describe as a unique personal connection to Florida voters. “It’s very hard to unify the state as a political figure,” Steve Schale, a Democratic operative who ran Obama’s Florida campaign in 2008, recently told New York. “But you can do it as a personality.”

Jeb Bush’s big political credential, and his presumed strength in the presidential campaign he’ll launch on Monday, is the broad appeal he demonstrated over two terms as Florida governor—doubly important given the critical role Florida’s primary will play in winnowing the GOP field. Bush handily won his last race, in 2002, by drawing support from Republicans and Democrats with what even his opponents describe as a unique personal connection to Florida voters. “It’s very hard to unify the state as a political figure,” Steve Schale, a Democratic operative who ran Obama’s Florida campaign in 2008, recently told New York. “But you can do it as a personality.”

Bush did it. But he may not be nearly as strong in Florida as his reputation suggests. A Bloomberg Politics study conducted with University of Florida political scientist Daniel A. Smith found that nearly three-quarters of Florida’s 12.9 million currently registered voters have never even seen Bush’s name on a ballot. “That’s a surprisingly large number,” says Smith, “which is due to a combination of low turnout and the turnover in the electorate over the 13 years since he was last on the ballot.” About 35 percent of voters in that election have disappeared from the state’s rolls—most have died, moved away or gone to prison. (Another group, thought to be much smaller, has been judged “mentally incapacitated” and stripped of the right to vote, although the Florida secretary of state’s office could not say precisely how many.) By contrast, 92 percent of Floridians who voted when Marco Rubio was last on the ballot, in 2010, are still registered.

Tracing the history of Florida’s 12.9 million registered voters to see who actually voted in Bush’s last race is difficult, because the state recently purged its voter histories before 2006. But Smith, using a 2002 voter history file he purchased from the state four years ago, determined that only 3.35 million people registered today also cast ballots in the 2002 general election—just over 25 percent. They include 1.52 million registered Republicans.

The steep drop off appears to be the result of a confluence of three demographic factors: age, transience, and crime. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Florida has the highest percentage of seniors (17.3 percent) in the country and one of the oldest populations of any state. In the 13 years since Bush last ran for office, many of those who pulled the lever for him have passed away. More than most states, Florida’s population is in constant flux. A 2010 Census Bureau report on lifetime mobility found that it is the most-transient state after Nevada, with just 35 percent of its residents being native-born. Finally, the U.S. Department of Justice lists Florida as having the nation’s ninth-highest incarceration rate, which removes another group—felons—from the voter rolls. (Contrary to popular perception, nobody I spoke with thought that the Floridians judged “mentally incapacitated” since 2002 numbered more than a few dozen.)

Does voting for a politician really produce the kind of personal connection that political operatives swear Bush had with Floridians? According to political scientists, it does. Wayne Steger of DePaul University, who specializes in presidential nominations, says the effect of having voted for someone is analogous to the incumbency advantage enjoyed by members of Congress. Scholars can measure this effect by studying congressmen whose districts are redrawn and comparing the level of support between voters they’ve previously represented and new ones added to their district. “When someone has voted for you before, it’s generally one of the great differentiators,” says Steger. “The more new voters they face, the smaller their incumbency advantage. [The new voters] haven’t experienced a previous campaign, so there’s a loss of familiarity.” Bush is in the odd position of being a famous former governor who nonetheless needs to re-introduce himself to the voters of his own state.

Even so, Bush can expect a built-in advantage in the Sunshine State, and not just with non-felonious Republicans who are longtime residents and mentally sound. “One aspect of the ‘favorite son effect’ is that they get a ton of favorable media coverage,” says Steger. “Local papers tend to cast their own candidates in very favorable terms, as we saw here in Illinois with Barack Obama.” Given Bush’s recent struggles and the turmoil in his political operation, any favorable coverage would be welcomed.

A bigger problem for Bush than dead or departed Floridians may be one who is very much alive—Marco Rubio. The senator’s presence in the race dilutes whatever “favorite son” effect Bush might have expected. And because he was elected less than five years ago, Rubio’s voter base hasn’t suffered the kind of attrition Bush’s has. Of the 5.46 million who voted in Rubio’s last election, 5.05 million remain eligible today—or 1.7 million more than are around from Bush’s last race. It’s all but certain that more Floridians have pulled the lever for Rubio than for Bush. So it may turn out that Florida’s “favorite son” isn’t a Bush at all.

http://www.newsmax.com/Politics/jeb-bush-floridians-never-saw/2015/06/14/id/650421/